Introduction | SIGNI SUBBOREALIUM GENTIUM

Introduction | SIGNI SUBBOREALIUM GENTIUM | SYMBOLS OF THE SUBBOREAL PEOPLES

1. The Notion of People

The people stand at the crossroads of several determinations upon which culture has acted and which have become harmonized. Its definition is therefore both cumulative and selective, because it preserves and innovates. Originally founded on ethnographic and linguistic traits, a people is also defined by a historical, social, and territorial heritage that cannot be reduced to any one of these dimensions alone. It constitutes a distinct human group that recognizes its unity by conceiving its own specific culture — its unique way of life. Although the terms nation, nationality, and people have been subject to many semantic distortions, they essentially refer to the same reality, differing only in degrees of development and organization.

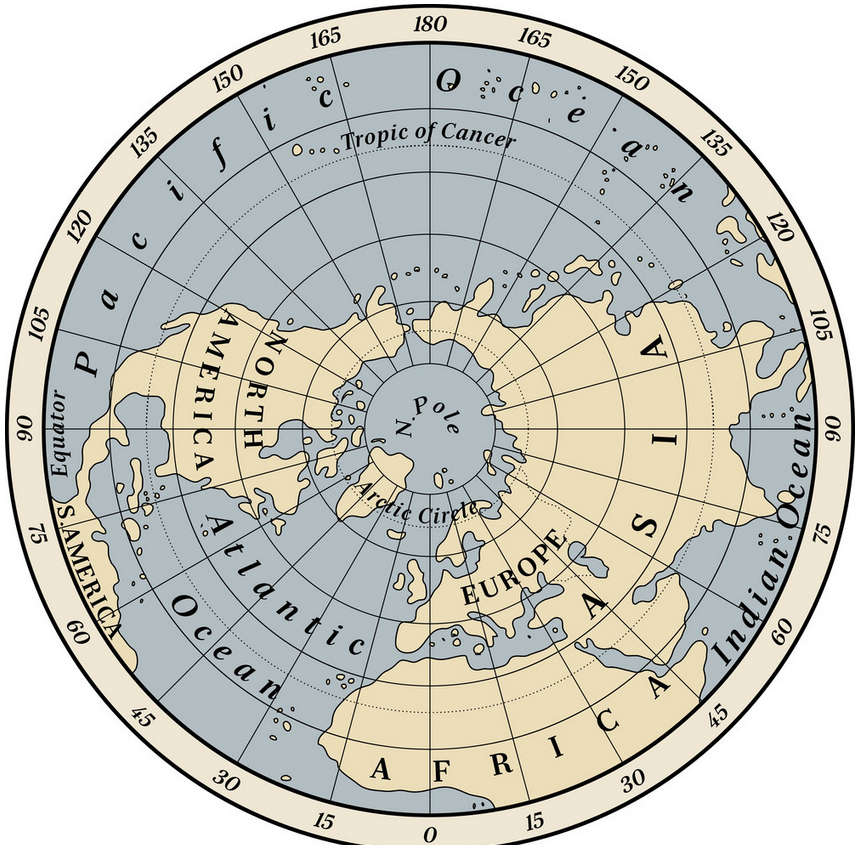

2. Peoples of the North

The peoples of the North, or Subboreans — “under Boreas” (the North or the North wind) — can be defined by their cultures and their ethnogenesis, which connect them and their distant ancestors to the regions north of the inhabited world, often for millennia. The states that currently encompass them also include other human groups with different traditions and origins. We have therefore paid little attention to state affiliations, which are too often arbitrary and subject to change.

The Subborean area studied here is properly referred to as the Ring of the North (an Arzhwalenn in Breton). It comprises three horizons:

-

Europa (Europe),

-

Siberia,

-

Northern America, or Erytheia boreia — an ancient Greek term meaning “the region tinged with red (i.e., toward the setting sun).”

The word symbol comes from the Greek súmbolon, meaning “sign of recognition by correspondence”.

3. Signs and Symbols

A symbol is most often an object (or a fragment of an object), an image, or a sign that refers, beyond its literal interpretation, to a reality such as an institution, a person or group, a quality, a concept, a function, etc., according to a principle of correspondence: the part standing for the whole, a formal analogy, a natural (the heart as the seat of feelings) or social function, or a conventional use (as in road or maritime signage). The circumstances in which a symbol originated are often forgotten, but the sign endures and represents the original reality.

In the context discussed here, signs have arisen through historical circumstances (an image of a fortress, the colors of a flag, an object imbued with powers). Some are designs that have been used for a very long time (the Irish Brigid’s cross). Others evoke a founding myth (the star of Italy). Included are also protective animals and emblematic flowers (England, Wallonia). The arrows of the Netherlands come from an allegory. Motifs in traditional embroidery are intimately tied to national identity, particularly in Eastern Europe.

Not all of these signs are contemporary. Some are based on traditional images inherited from a distant past (the trident of the Greeks); others have been reinterpreted (the medieval Saint Andrew’s cross). Some cannot be dated, as they are timelessly associated with the life of a people and its ecosystem (migratory geese of the northern Siberian peoples, suns, stars, trees). Symbolic activity takes place within the framework of a coherent tradition (meanings vary between major cultural spheres). This tradition — “what is transmitted and renewed with each generation” — gives the signs their full significance. Peoples spontaneously associate the signs of their culture with their artistic activities, their social aspirations, and their collective achievements.

Each people can be represented by a symbolic graph. This is a small sign based on simple geometric forms, easily reproducible and justified by an undeniable tradition — even when its design innovates by updating ancient motifs. Unlike coats of arms, which are sometimes complex, or flags distinguished by their colors, ethnograms can be rendered both in monochrome and in multiple colors. Their use is recommended for badges, engraving, and modern signage. To design them, we drew on historical traditions, on popular graphic arts such as embroidery and wood engraving, and on customary usage that has established their legitimacy.

Each major geo-cultural area has its own distinctive mark and color scheme, more or less confirmed by use and, above all, by civilizational consciousness.

For example: in Asia, the yin-yang; in the Altaic area, the supratribal proto-tamga (A. E. Rogozhinsky and D. V. Cheremisin, Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, 47/2, 2019, pp. 48–59, fig. 6); in the Hamito-Semitic world, the star and crescent; in sub-Saharan Africa, the spear and the hoe.

4. Signs of the Subborean Horizons

The symbol common to all three Subborean horizons is the sign of the pole: the Pole Star and the Little Bear (Ursa Minor) in its celestial position at the spring equinox — a reference in the vexillology of Northern Hemisphere countries equivalent to the Southern Cross for those of the antipodes.

Their respective symbols are:

-

for Europe, the Tree of Worlds (explained below);

-

for Siberia, the wild goose, reindeer antlers, and snow crystal;

-

for North America, the Amerindian image of Venus and the arrows.

The three horizons of the Northern Ring are associated with the East, the South (the Sun’s point of culmination), and the West, according to ancient conceptions embedded in language and myth.

-

The color of the East is that of dawn — orange;

-

The South is linked to sky blue;

-

The West, Erytheia, bears the symbolic color of deep red.

For the polar regions, the alternation of night and day entails the two fundamental values of black and white.