Présentation

The Greeks, or Hellenes (Hellas: Herodotus 6.98 and 1.92; Strabo, 253), ‘the solar Ethnos’, traced their mythical descent to Hellen, son of Deucalion and Pyrrha, father of Xouthos, Doros, and Aeolus, the respective ancestors of the Achaeans and Ionians, the Dorians, and the Aeolians. Coming from the Northwest (Epirus), the Hellenes succeeded other Indo-Europeans, the Pelasgoi (to be compared with the Pelaistoi of Attica).

A language whose written evolution can be followed since the decipherment of ‘Linear B’ (dated to the 13th century BCE, a primitive stage close to Achaean and Arcadian), Greek had as its principal dialects Arcado-Cypriot, Ionic, Aeolic (Alcaeus, Sappho), and the various so-called Doric dialects (Pindar, Theocritus), ancestors of Tsakonian of the eastern Peloponnese. Ionic, mixed with Aeolic elements, forms the basis of the Homeric poems.

Customs and love of the nourishing soil, aroura, ‘warm land, deep land, bitter land’, ‘mother magnanimous in pain and glory (…) / divine homeland all covered in blood’ (Y. Ritsos), sustain a people placed by history at the forefront of European culture.

The integration of the Hellenic peninsula into the Roman Empire, the proximity of the Slavs, and the separation of Rome and Byzantium profoundly shaped the condition of the ethnos, Romiosyni, while resistance to Ottoman and Muslim conquest in Anatolia and then on the very soil of the Balkans strengthened national consciousness and prepared modern independences (1830 for Greece): ‘Here it is, it leaps forward and is reborn and regains strength and vigor / and harpoons the monster with the sting of the sun’ (Y. Ritsos). The Treaty of Bucharest (1913) and the incorporation of the Dodecanese (1947) brought only an imperfect end to the national question: Eastern Thrace, Constantinople, and part of Cyprus remain under Turkish administration and occupation.

The Greek state essentially shelters the eponymous people of Hellas, alongside Albanian, Aromanian, and Slavic-speaking minorities. Greek communities are found in Albanian Epirus, in Italy in Apulia and Calabria (the Griko dialect), as well as in Sicily and at Cargèse in Corsica. Around the Black Sea (Pontus Euxinus), the Pontic Greeks (Póntioi) were largely deported, first following the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, which extended the Treaty of Versailles, and then by the Soviets in 1944. In Bulgaria, the Greek-speaking Karakachans (Sarakatsánoi in Greece) have the status of an ethnic group.

In 1822 the Greek flag displayed the Greek cross (with equal arms) in white on a blue field of the arms. In 1833 it appeared in the canton. The state coat of arms is surrounded by olive branches, a pan-Hellenic symbol. The flag of the Pontic Greeks is gold, charged with the black eagle of Sinope within a fine black circle.

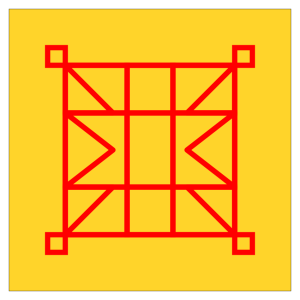

Here we present a motif composed of the double-bladed axe (associated with lightning; see J. Déchelette, Manuel d’Archéologie préhistorique, celtique et gallo-romaine, vol. II, Paris, 1910, pp. 480–484; M. P. Nilsson, The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion, 2nd ed., Lund, 1950, pp. 195–220; S. Alexiou, La Crète minoenne, Heraklion, p. 87) and the trident (maritime) of Poseidon.

Location

-

Municipal Unit of Tithorea, Amfikleia-Elateia Municipality, Phthiotis Regional Unit, Central Greece, Thessaly and Central Greece, 350 15, Greece

Add a comment