Description

The peoples of Germanic languages today extend from England to Scandinavia, from the Flemish Aa to the course of the Oder, from the Vosges to the Alto Adige. Linguistically, one distinguishes the northern area; the western or Anglo-Frisian; the German–Dutch; the High German; and the Austro-Bavarian, with numerous transitional dialects.

Mythically, the Germanic group (Germanoi, Posidonius as cited by Athenaeus, IV, 153) brings together the descendants of Mannus, son of Tuisto, father of the three tribes of the Ingaevones, the (H)Erminones, and the Istaevones (Tacitus, Germania, 2). As a catalyst of peoples, the Germanic expansion of Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages profoundly shaped Europe’s political forms: settlements of the Goths (from the Swedish Götaland) on the Baltic and the Vistula (1st–4th c.), and even in Crimea (Gothic language); the Visigoths of Toulouse and Hispania; the Frankish kingdoms of Roman Gaul; the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes of Britain (6th c.); Frisian and Scandinavian colonies; Norse settlements in Normandy (8th c.) and Sicily; the Varangians of Rus’ (Kiev and Novgorod in the 8th and 9th centuries); the states of the Burgundians and the Lombards. For the historian Jordanes (5th c.), Scania or Scandinavia (from Swedish skåne “island”) of the northern Germani constitutes the vagina gentium of Antiquity and the early Middle Ages.

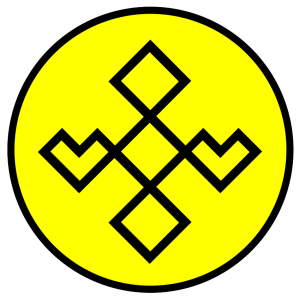

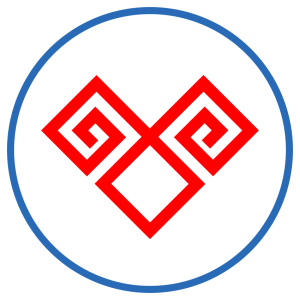

A common Germanic artefact is the circle with nine waves, an ornamental and mythological image expressing the notions of community and the movement of life. Interlace and various knot patterns are major figures of Germanic art in the early Middle Ages. Through their later artistic and craft developments, they provided a privileged symbol to the various branches of this family. The “endless knot” and circularity are characteristic of tendencies in Germanic art—an art that evokes the indefiniteness of becoming through its overflowing linear motifs, but also the notion of solidarity within communal bonds. (On these conceptual foundations, see J. de Vries, Die geistige Welt der Germanen³, Darmstadt, 1964 = L’univers mental des Germains, Paris, 1987, p. 190.)

Here we depict the ancient interlace motif known by the popular name shieldknot, which produced numerous variants throughout the Germanic world, including the exemplary type of the circular fibula from the princely tomb of Wittislingen in Swabia, 7th century AD.

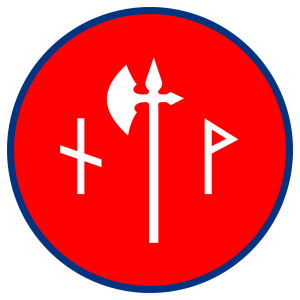

► Regarding the symbolism of the Germanic peoples, the use of runic characters is possible when needed. This is an ancient signary, correlated—beginning in the 1st century AD—with the characters of southern alphabets (probably Alpine), and used thereafter as a script, alongside various cultic, magical, and calendrical uses. Each sign corresponds to an acronym (a name beginning with the indicated sound, such as fehu “cattle” for ᛓ F). When the heraldic emblem is not sufficiently distinctive by itself and when no other geometrically economical possibility exists, one employs the initial rune or runes designating the country in question, according to the ancient principle of the acronym.

► The flags of the Scandinavian peoples and certain Finnoid peoples bear the Scandinavian cross called the “Cross of Saint Olaf,” which follows the layout of the constellation Cygnus, also called the Crux Major and the “Northern Cross,” whose main axis runs from Deneb (α) to Albireo (β), the “eye of the swan” (the swan’s head—an animal with a long neck—corresponds to the foot of the ‘cross’).

Add a review